The Right Editor for the Right Job

Think of an editor as a medical professional. If you have an infected foot, a brain surgeon may not be helpful. Your manuscript must have vitality, to be submittable or published independently; it must be fit, throbbing with life, well-formed, well-groomed, and dressed in its Sunday best. The editor needed for the job depends on where you are on your path to print.

Post Second Draft Check up – Manuscript Critique

You’ve survived your first round of revisions, cleaned up obvious errors, filled story holes, polished tone and pace, and digested feedback from beta readers. Now what? Time to put on your big writer pants and seek a professional. Genre is key to finding the right (write) editor. If the editor is neither experienced nor aware of your market, save your money. Find an editor well versed in your genre. If you write memoir, you want a seasoned creative non-fiction editor, not a fantasy/sci-fi editor.

What can you expect from a manuscript critique? The editor is an attentive reader who provides feedback regarding content. Think of it as a physical. Expect a 5-10 page report that highlights the health of your work — both the good and possible trouble points. Anticipate criticism and comment about the opening, structure, POV, style, pace, dialogue, and ending. Specific pages, passages, and plot points will be highlighted. Is the work compelling, does it work as a whole, and if not, what steps need to be taken? Prepare to be relieved, with moments of associated delight and terror.

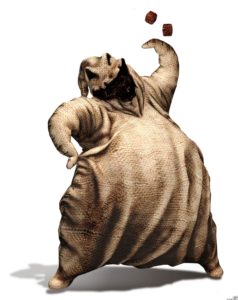

Terrified about what a manuscript critique might cost? Editing, like a good diet, is an iterative process. The more you improve your practice, the better you can manage the ultimate cost.

Identify your writer’s habits. with the help of an editor/writer’s coach. Your habits: qualifying phrases, word overuse, complicated dialogue attributions, a preference for stutter verbs, voice shifts, adequate pace, and characterization can be identified in as little as three chapters. The editor will mark up the work with highlights and suggestions. It is up to you scan your full document for other examples and make corrections to achieve the third draft. The cleaner the draft, the more focus on content by a developmental editor.

Developmental Editing – Penultimate Draft

If a manuscript critique is equivalent to a physical at a GP, a developmental edit is on par with a full work up at the Mayo Clinic. You look for a developmental editor when you have taken the manuscript as far as you can toward a goal of submission or independent publishing. Expect in-depth feedback on all issues: word use, historical accuracy, questions regarding writer’s choices, under or overdeveloped characters, pace, a tone in keeping with the genre, marketability, and praise for strengths. Don’t waste your money on developmental editing if your work is not ready. Patients do not go to the Mayo Clinic for hangnails or two or three bouts of indigestion.

Copyediting – Final, Final

You can be a brilliant writer but be a horrible technician. I’ve coached many writers who insist on creating their own document structure rather than follow standard submission guidelines. A unique document structure may feel creative at the beginning of a draft, but it is hell to clean up at the end. Ignoring structure and punctuation rules is like living on Tostitos and soda until 5:00 and happy hour appetizers and alcohol until bedtime for ten years. A seven-day detox will not correct the underlying and long-term issues. Writing is a practice. Copyeditors are perfectionists. They want every comma, paragraph indent, en dash, and period in its proper place. Many a prospective agent has dismissed a manuscript for sloppiness, not content.

Many a Mayo Clinic visit is built on a foundation of bad choices. Ensure that your work is the best you can make it for a clean bill of health. A strong, healthy, and clean manuscript increases publication chances and happy readers.

Writing is hard. Go to any social media site and you’ll see posts from writers who declare that they want to write but don’t. Others wait for divine inspiration and express frustration at their lack of ideas. Still more, state for public consumption that what they write is drek.

Writing is hard. Go to any social media site and you’ll see posts from writers who declare that they want to write but don’t. Others wait for divine inspiration and express frustration at their lack of ideas. Still more, state for public consumption that what they write is drek.